Fort Street originated as Fort Place in the 1905 plat of Lawton Park, an Addition to the City of Seattle. It originally formed part of the “government roadway leading from the east boundary of the military reservation of Fort Lawton,” but in 1961 four of its blocks were officially renamed W Government Way. What remains today is a one-block stretch between 36th Avenue W and 35th Avenue W, a three-block stretch between Kiwanis Memorial Reserve Park and 32nd Avenue W, and a bridge over the BNSF Railway tracks from 28th Avenue W and Gilman Avenue W to 27th Avenue W.

W Government Way

In 1897 a number of Magnolia landowners deeded to the federal government land for “a government roadway leading from the east boundary of the military reservation of Fort Lawton,” which was to open in 1900, to a wharf at what is now 27th Avenue W and W Commodore Way. At some point between then and 1907, when it appears in in the plat of Lawton Heights, an Addition to the City of Seattle, filed by Anna S. Brygger (see Brygger Drive W and NW Brygger Place), it became known as Government Way. (There are similarly named streets in Spokane leading to the former Fort George Wright and in Coeur D’Alene, Idaho, leading to the former Fort Sherman.)

The street was initially known as Government Way only from 32nd Avenue W to the east gate of the fort at 36th Avenue W (now the main entrance to Discovery Park), but in 1961 the name was extended to cover 32nd Avenue W north to W Fort Street as well as W Fort Street east to Gilman Avenue W, so today its length is about ½ a mile in total.

Perkins Lane W

This Magnolia street boasts one of the best views in all of Seattle — a completely unobstructed vista of Elliott Bay, Puget Sound, the Kitsap Peninsula, and the Olympic Mountains — if you’re fortunate enough to own property there. The view from the street itself is mostly of houses to the west, forested slope to the east. Notable Seattleites such as developer Martin Selig, broadcaster Kathi Goertzen, musician Ryan Lewis, and co-founder of Starbucks and Redhook Ale Brewery Gordon Bowker have called the winding lane — and it truly is a winding lane, hugging the bluff with barely enough room for two cars to pass each other — home.

The street was created as part of Carleton Beach Tracts, an Addition to the City of Seattle, Washington, on New Year’s Eve, 1920. The owners were Arthur Alexander Phinney (1885–1941), son of Guy Carleton Phinney, after whom Phinney Ridge and Phinney Avenue N are named; his wife, Daisy Euphemia Phinney (1884–1950); the Phinney Realty and Investment Company; and Oscar E. Jensen & Co., Inc. It begins at W Emerson Street in the north, just south of Discovery Park, and goes 1⅖ miles southeast to a roadblock a few feet beyond the bottom of the Montavista Stairs (more on that later). The roadway continues about 250 feet past the roadblock — all the buildings and lots on the west side belong to Martin Selig — and the right-of-way continues a little over 800 feet beyond that (see below for why).

The lane’s namesake had been a mystery to me for a long time, until I came across the Phinneys’ wedding announcement in the May 11, 1913, issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

Formal announcement made yesterday of the marriage at Victoria, B.C., May 2, of Miss Daisy E. Perkins, of Portland, to Mr. Arthur A. Phinney, of Seattle, contained the first intimation to local friends of Mr. Phinney of the nuptial event. The bride and groom had laid their plans in secret and protected this secret against all inquiring friends.

It seems, then, that we have a case similar to that of Thorndyke Avenue W — naming a prominent street after the wife’s maiden name.

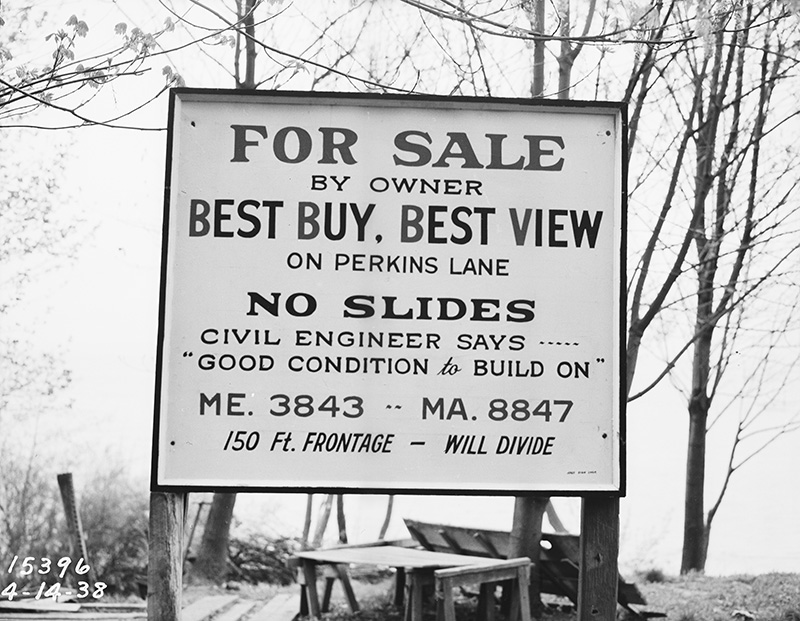

For all its advantages, though — view, privacy (though it’s a public street, there are only a couple of ways to drive there from the rest of the city, plus two rickety staircases down from Magnolia Boulevard) — Perkins Lane has its faults, as the headline ‘Perkins Lane: Seattle’s Poster Child for Landslide Risk’ implies. A major landslide at the end of 1996 took out five or six houses, depending on whom you ask, at the southeast end of the street, and the adjoining roadway — hence the aforementioned roadblock. A lawsuit against the city, of course, was filed, but was dismissed at summary judgment. Slides had been a problem for the seven decades of Perkins Lane’s existence before that, as the images below attest. (The statute of limitations for false advertising has long elapsed, alas…)

“No slides — Civil engineer says ‘Good condition to build on,’” 2461 Perkins Lane W, April 14, 1938. Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Identifier 12194

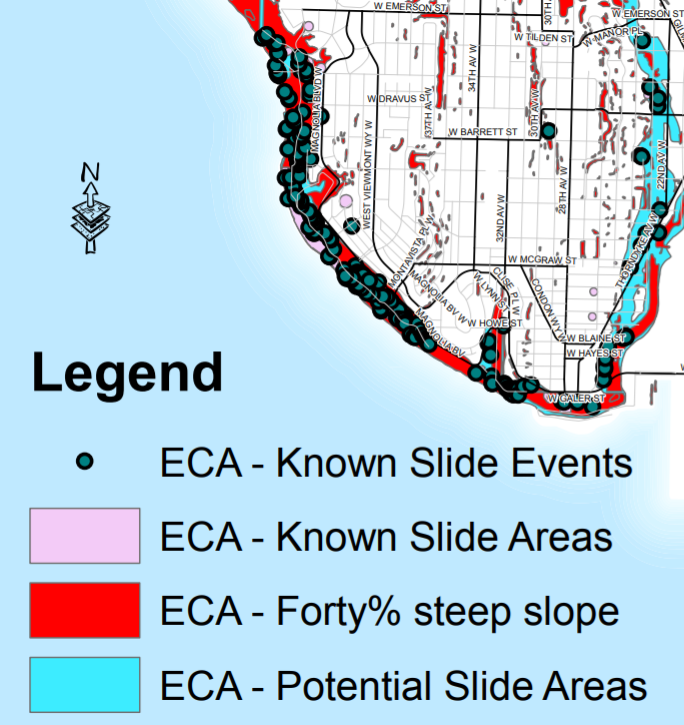

In fact, as the map below shows, there have been numerous slides over the years along the entire length of the road.

Perkins Lane W is also home to six of Seattle’s shoreline street ends — at W Bertona, Dravus, Barrett, Armour, Raye, and McGraw Streets, though McGraw is the only one currently accessible from land. The project to improve it back in 2013 and 2014 was not without opposition, but ultimately the threats never materialized (nor did the opponents’s fears). It’s well worth a visit.

W Marginal Way SW

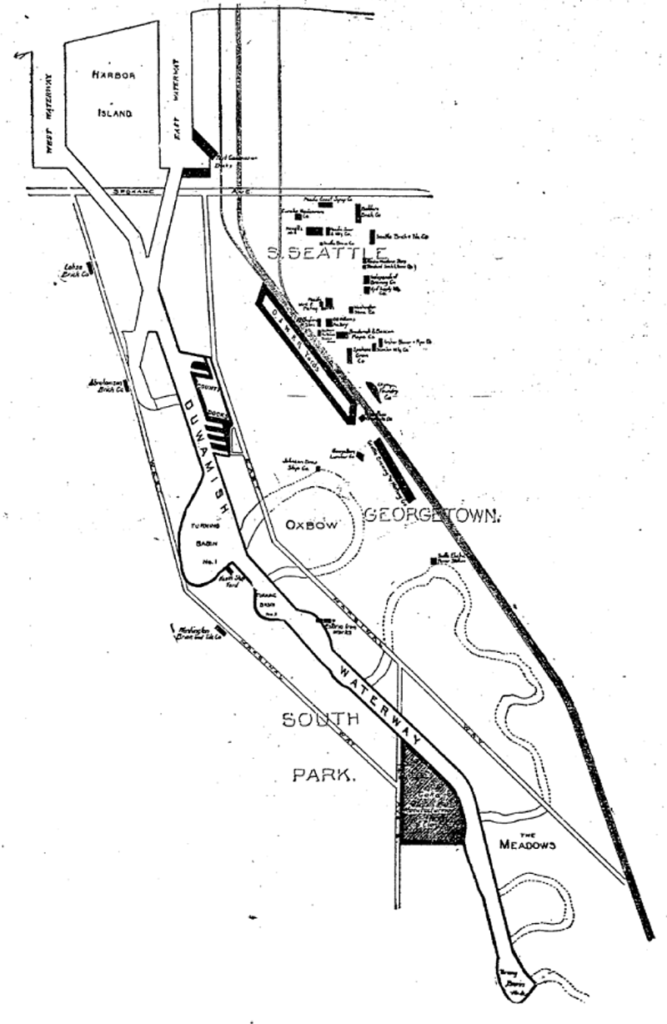

W Marginal Way SW, like its twin across the water, E Marginal Way S, began literally as a “marginal way” to “give railroads, street cars and other transportation facilities access to the Duwamish waterway.”

W Marginal Way SW begins at 26th Avenue SW at the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 5. From there, it’s 3 miles southeast to 2nd Avenue SW, by the south end of the 1st Avenue S Bridge. It resumes on the east side of the bridge as W Marginal Way S, an extension of Highland Park Way SW, and runs 4⅖ miles from there to the southern city limits. (For all but the first few blocks of this stretch, it is a limited-access highway carrying Washington State Route 99.) Beyond there it runs 3½ miles more to the vicinity of an interchange with Tukwila International Boulevard. The name is dropped at this point (and does not appear on signs south of the initial few blocks); the highway continues 1¾ miles as Washington State Route 599 to Interstate 5.

Copyright © 2010 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved.

W Marginal Way S is the location of the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, across the street from həʔapus Village Park and Shoreline Habitat (formerly Terminal 107 Park). həʔapus, or x̌əʔapus, was the name of a Duwamish village that was burned down by settlers in 1895. The new longhouse became the first one within city limits in 114 years. Notably, descendants of settlers Charles Terry and David Denny participated in fundraising and advocacy, without which the project would have been impossible, as the Duwamish were forced to purchase back the land. (A good article for more detail is “On the Duwamish River, a longhouse rises,” which appeared in Real Change in March 2009.)

E Marginal Way S

E Marginal Way S and its twin across the Duwamish Waterway, W Marginal Way SW, are good examples of purely descriptive Seattle street names. In fact, they are first mentioned in the press as adjective + noun, not name + type:

- “Marginal ways are urged for both sides of Duwamish waterway.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 27, 1911, in reference to the Bogue Plan

- “Coincident with the completion of the Duwamish waterway and the wide marginal streets on each side, a publicly owned railway should be built along these marginal ways…” C.C. Closson, realtor and the Port of Seattle’s first paid employee, in a letter to the editor, Seattle P-I, July 8, 1912

- “East and west marginal ways, planned by Bogue to parallel the waterway to give railroads, street cars and other transportation facilities access to the Duwamish waterway, will both pass through Oxbow.“ The Seattle Times, March 26, 1914

- “Marginal ways parallel the new waterway for the whole distance, connecting with the main streets of the city running to the south.” Seattle P-I, August 13, 1914

A longer excerpt, from an article in the April 19, 1914, issue of The Seattle Times, explains the reason for their creation:

Second only in importance to the waterway are the projected traffic streets, east and west marginal ways, laid out on both sides of the waterway about 1,000 feet back to give railways and street car lines the opportunity to parallel the waterway on both sides for its entire length, to give service to the industries locating along the waterway. As an allowance of $175,000 was made for East Marginal Way in the $3,000,000 county bond issue for roads, that street is now being condemned by the city and will be constructed 130 feet wide to the south city limits, where it will join a county road. West Marginal Way is also being promoted by interested property owners. As the existing railways are already but a short distance east of the Duwamish River, spurs can be thrown into East Marginal Way at slight expense. Also the port commission is considering a plan for port district terminal tracks on the Marginal Ways to serve the waterway.

The Duwamish Waterway, whose construction began on October 14, 1913, was a straightening and deepening of the last 6 miles of the formerly meandering river. Construction of the waterway, with Harbor Island at its mouth (the largest artificial island in the world from 1909 to 1938), plus the filling of the Elliott Bay tidelands, are what give Seattle’s harbor its modern shape.

E Marginal Way S begins as an extension of Alaskan Way S — originally Railroad Avenue, which served much the same function for the central waterfront — at the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 30, and stretches 4⅖ miles from there to the southern city limits. (From the southern end of the Alaskan Freeway to the northern end of the 1st Avenue South Bridge, it carries Washington State Route 99.) Beyond there it runs 3½ miles more to S 133rd Street in Tukwila.

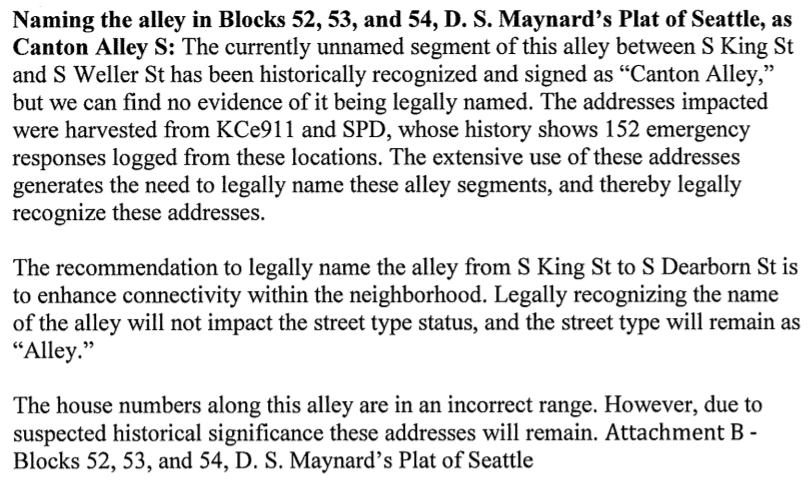

Canton Alley S

Canton Alley, twin to Maynard Alley a block to the west, is another one of the few named alleys in Seattle. It goes just under ⅕ of a mile from S King Street in the north to S Dearborn Street in the south, between 7th Avenue S and 8th Avenue S.

Similar to the one in Vancouver, British Columbia, it was named after the city and province of Canton in China, today known as Guangzhou in Guangdong province, from where the majority of Chinese immigrants to Seattle came.

As with Maynard Alley, even though Canton Alley had been called that for years, and was signed as such, its name was not officially made Canton Alley S until 2019, so that addresses from which 911 calls were coming could be more easily located and emergency vehicle response times could be reduced.

(The earliest reference I can find to Canton Alley in The Seattle Star, The Seattle Times, or the Seattle Post-Intelligencer is an article in the February 12, 1911, issue of the Times.)

One major difference between Canton and Maynard Alleys is the house numbers, as mentioned in the excerpt from the summary and fiscal note to the ordinance above. House numbers on Maynard Alley S follow the standard pattern; the 500 block of Maynard Alley is the one south of S King Street, due west of the 500 block of 7th Avenue S, that of 8th Avenue S, etc. But house numbers on Canton Alley S follow the “European system” (also used in American cities like New York), so very low addresses such as 9 Canton Alley S exist — quite rare in Seattle — and were not changed by the ordinance.

Maynard Alley S

Maynard Alley, one of the few named alleys in Seattle, goes just under ¼ mile from S Jackson Street in the north to S Dearborn Street in the south between Maynard Avenue S and 7th Avenue S. Like Maynard Avenue, it was named for David Swinson “Doc” Maynard, who is generally credited with naming the town of Seattle, after his friend siʔaɫ, or Chief Seattle, and was its “first physician, merchant, Indian agent, and justice of the peace.”

Even though it had been named that for years, and was signed as such, its name was not officially made Maynard Alley S until 2019, so that addresses from which 911 calls were coming could be more easily located and emergency vehicle response times could be reduced. (The same thing was done for Canton Alley S, a block to the east, as part of the same ordinance.)

(The earliest reference I can find to Maynard Alley in The Seattle Star, The Seattle Times, or the Seattle Post-Intelligencer is an article in the March 30, 1910, issue of the P-I.)

S Royal Brougham Way

This street begins at Colorado Avenue S in the west, at an onramp to the northbound lanes of the State Route 99 tunnel, and goes ⅔ of a mile east to Airport Way S. Originally S Connecticut Street, it was renamed in 1979 in honor of sportswriter Royal Brougham (1894–1978), who worked for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper from 1910 until his death. Such a name change was formally proposed by city councilman George Benson following a suggestion by P-I columnist Emmett Watson. Originally it was to be Occidental Avenue S whose name was to be changed, then the 2nd Avenue S Extension when objections were raised. Finally S Connecticut Street was settled upon; it was thought to be particularly appropriate because he “worked so hard to see the Kingdome built… and eventually spent his last day on earth there.”

Lumen Field, built on the former Kingdome site, is on the north side of Royal Brougham between 1st Avenue S and 4th Avenue S; and T-Mobile Park is on the south side between 1st Avenue S and 3rd Avenue S.

Troll Avenue N

When the George Washington Memorial Bridge (more commonly known as the Aurora Bridge) was opened in 1932, a stretch of Aurora Avenue N, unconected to the highway, remained underneath its north approach. This remained the case for 73 years, until its name was changed to Troll Avenue N in 2005. The street — only two blocks long, from N 34th Street to N 36th Street — was renamed as part of the Fremont Neighborhood Plan, which called for the Fremont Troll, located at 36th and Aurora, as a “unifying theme” for the neighborhood, and to improve wayfinding — someone unfamiliar with the area looking for the 3500 block of Aurora Avenue N, say, would be likely to find themselves on the bridge instead of the local street.

Borealis Avenue

In 1948, when Aurora Avenue N (then U.S. Route 99) was being readied to connect to the under-construction Alaskan Way Viaduct, it was extended a block south of Denny Way to 6th Avenue and Battery Street, creating a short stretch of Aurora Avenue with no directional designation. This remained the case until 2019, when the replacement tunnel for the viaduct opened. At that time, Aurora south of Harrison Street reverted to its earlier name of 7th Avenue N, and since 7th Avenue south of Denny Way already existed, a new name was needed for the block-long Aurora Avenue.

According to The Urbanist, “Borealis,” referring to the aurora borealis, was a community favorite — but it was named after a nearby apartment building, not after the northern lights directly. As for why the names were changed in the first place, The Seattle Times reported that it was felt there were “negative connotations associated with [the name] Aurora Avenue” they wanted to avoid while reintegrating this stretch of the road into the neighborhood.

Aurora Avenue N

What is now Aurora Avenue N began in 1888 as Aurora Street in Denny & Hoyt’s Addition to the City of Seattle, Washington Territory, previously discussed in our post on Dravus Street. Edward Blewett and his wife, Carrie, of Fremont, Nebraska, were the landowners, and Edward Corliss Kilbourne (1856–1959) filed the plat as attorney-in-fact for the Blewetts. Dr. Kilbourne (a dentist), was from Aurora, Illinois, and it seems to be generally accepted (The Fremocentrist, Wedgwood in Seattle History, Fremont Neighborhood Council, Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle) that he named the street after his hometown.

(I have seen elsewhere [HistoryLink, Washington’s Pacific Highway], that Aurora was given its name sometime in the early 20th century by George F. Cotterill, mayor of Seattle from 1912–1914, because it was “the highway to the north, toward the aurora borealis,” but they have the century wrong, and Aurora Street was no highway in 1888. In addition, those two pages call him “city engineer, later mayor,” but he was never city engineer — although he was assistant city engineer from 1892–1900. The Licton Springs Community Council mentions both theories.)

At any rate, Ordinance 6947, filed on June 6, 1901, refers to the street as Aurora Street, and Ordinance 7942, filed on November 5 of that year, refers to it as Aurora Avenue. I can find no specific record of the name change, but Ordinance 6864, filed on May 8, has to do with “altering, defining and establishing the names of streets in the City of Seattle in the portion thereof lying north of Lake Union, Salmon Bay and the route of the Lake Washington Canal,” and is likely responsible. (No text is available online for the ordinance, and the drafters of Ordinance 6947 must have neglected to take the change into account.)

Aurora Avenue N might have remained just another North Seattle street were it not for the decision to route the Pacific Highway, U.S. Route 99, across the Lake Washington Ship Canal there instead of Stone Way N, Albion Place N, Whitman Avenue N, or Linden Avenue N. As it happened, Aurora was chosen as the location for the crossing (known today as the Aurora Bridge), and the name was officially extended through Queen Anne to Downtown Seattle in 1930 in preparation for the bridge’s opening in 1932.

Added July 14, 2023: I spoke to Feliks Banel of KIRO Newsradio for one of his All Over the Map segments, this one on how the Aurora Bridge got its name. I didn’t appear on air, but was mentioned in both the audio and web versions of the story.

Today, Aurora Avenue N begins at 7th Avenue N and Harrison Street by the north portal of the State Route 99 Tunnel and goes 7⅘ miles north to the city limits; the name continues 3 further miles to the King–Snohomish county line, and the highway another 12 miles beyond that to Broadway in Everett. A block-long segment from 6th Avenue and Battery Street to Denny Way has been renamed Borealis Avenue, and Aurora between Denny Way and Harrison Street is once again 7th Avenue N. A two-block-long segment underneath the north approach to the Aurora Bridge has also been changed to Troll Avenue N.

S Roberto Maestas Festival Street

This street, formerly the 1600 block of S Lander Street, runs between 16th and 17th Avenues S on Beacon Hill, north of the Beacon Hill light rail station and south of the Plaza Roberto Maestas housing development of El Centro de la Raza, a social service agency. It was renamed in 2011 in honor of Roberto Maestas (1938–2010), who co-founded El Centro in 1972 in the recently closed Beacon Hill Elementary School.

The street is one of a number of “festival streets” in the city of Seattle: “designated portions of streets intended for frequent public events.” E Barbara Bailey Way is the other one we’ve covered so far.

Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE

This street, which runs ⅕ of a mile from the “five corners” intersection with NE 45th Street, NE 45th Place, and Union Bay Place NE in the northwest to NE 41st Street in the southeast, was created in 1911 as an extension of Union Bay Place. It was renamed in 1995 in honor of Mary Maxwell Gates (1929–1994), mother of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and a member of the University of Washington Board of Regents from 1975 to 1993.

The original proposal was to also change the name of NE 41st Street between Union Bay Place NE and Surber Drive NE to NE Mary Gates Memorial Drive, but this was not done. An article in the March 14, 1995, issue of The Seattle Times reports that “City Councilwoman Sue Donaldson said the Laurelhurst Community Club, the university and its neighbors near Union Bay Place Northeast joined yesterday in asking” for the name change, and an article in the September 1995 issue of Columns, then the name of the University of Washington alumni magazine, reports Donaldson as saying “The new name is particularly fitting… because it was the route Gates took from home to campus.”

I have never seen an explanation as to why the proposed name wasn’t simply Mary Gates Drive NE — it is the only “memorial” thoroughfare in town.

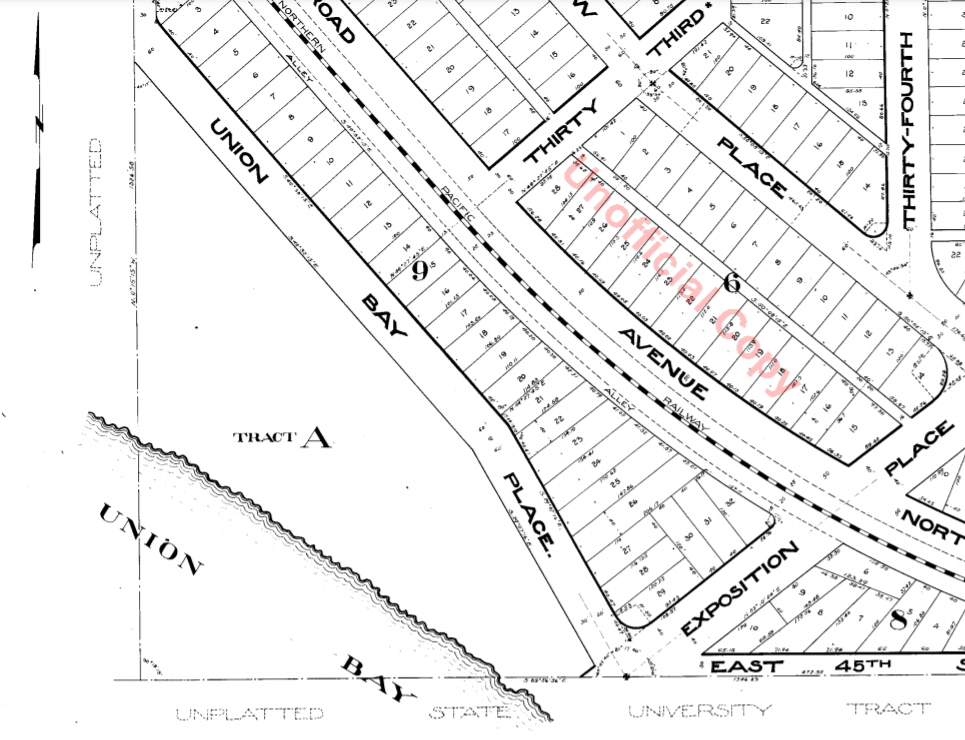

Union Bay Place NE

This street, which runs ⅕ of a mile from 30th Avenue NE in the northwest to the “five corners” intersection with NE 45th Street, NE 45th Place, and Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE, was created in 1907 as part of the Exposition Heights addition. Four years later, the street was extended southeast of NE 45th Street through University of Washington property to NE 41st Street. However, in 1995 that portion was renamed Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE.

As can be seen in the map below, it did once parallel Union Bay; however, when the Montlake Cut of the Lake Washington Ship Canal opened in 1916, the lake and bay dropped by 8.8 feet to match the level of Lake Union and this was no longer waterfront property. The southwest corner of this map is now entirely devoted to commercial and residential use.

Union Bay itself was named in 1854 by settler Thomas Mercer, with the idea that it and Lake Union, which he also named, would one day be part of a connection from Lake Washington to Puget Sound. As mentioned above, this did end up happening 62 years later.

Stanford Avenue NE

Another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928, Stanford Avenue NE was named for Stanford University in Stanford, California. It runs ⅓ of a mile in a semicircle from NE 60th Street near 45th Avenue NE in the west to NE 60th Street at 50th Avenue NE in the east.

Oberlin Avenue NE

Oberlin Avenue NE is another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928. It was named for Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and runs around ⅕ of a mile from 45th Avenue NE in the northwest to Princeton Avenue NE in the southeast.

Wellesley Way NE

Wellesley Way NE is another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928. It was named for Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and runs around ⅕ of a mile from NE 65th Street in the north to NE 60th Street and Ann Arbor Avenue NE in the south.

Vassar Avenue NE

Vassar Avenue NE, another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928, was named for Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. It runs almost ⅖ of a mile from NE 65th Street in the northwest to Stanford Avenue NE in the southeast.

Ann Arbor Avenue NE

Another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928, Ann Arbor Avenue NE was named for the University of Michigan, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It runs nearly ½ a mile from Pullman Avenue NE in the south to NE 65th Street in the north.

Purdue Avenue NE

Purdue Avenue NE is another one of the “university” streets in the Hawthorne Hills subdivision, created in 1928. It was named for Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. It runs almost ½ a mile from NE 58th Street and 45th Avenue NE to from NE 60th Street and 51st Avenue NE.