Since the killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, set off a wave of protests and demonstrations that has not yet abated, calls to rename streets dedicated to Confederate leaders have grown ever louder. Among them are Robert E. Lee Boulevard and Jefferson Davis Parkway in New Orleans; Confederate Avenue in Tyler, Texas; Stonewall Jackson Drive and Bedford Forrest Drive in Wilmington, North Carolina; and Stonewall Jackson Drive and General Lee Avenue in Fort Hamilton, a U.S. Army base in Brooklyn.

In Montgomery County, Maryland, the county council has called for “a comprehensive review of all County owned and maintained street names and public facilities to determine all those named for Confederate soldiers or those who otherwise do not reflect Montgomery County values.” The pull-quotes WTOP News chose from the council’s letter were spot-on:

As we work to dismantle the structures that perpetuate racism, we must target the symbols that normalize and legitimize it. The names of public streets and buildings are not merely a reminder of the past; they are a very clear indication of who and what we value today.… We cannot recreate history, but we can decide how accurately we reflect it, and who we choose to glorify from it. The names of our buildings and streets should reflect the people in and on them, not threaten and intimidate them.

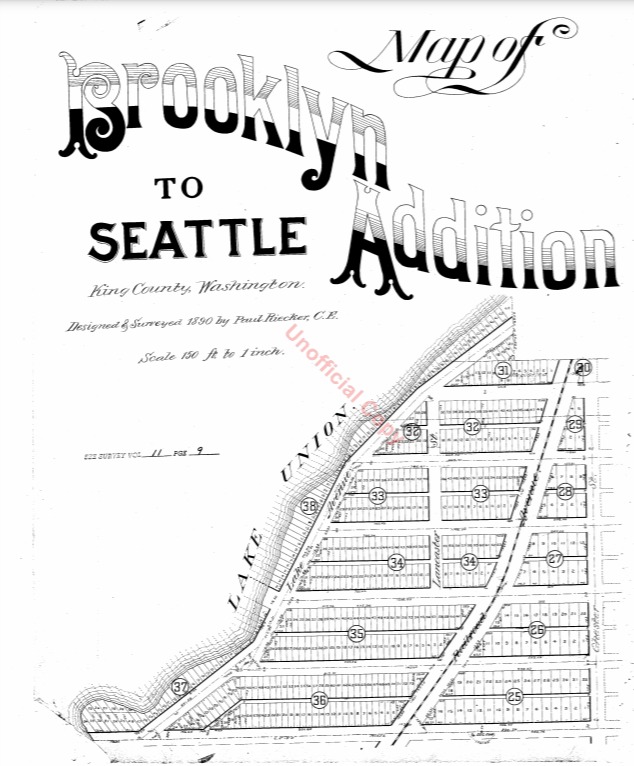

Calls for renaming Seattle streets haven’t been as loud — perhaps because we, fortunately, have none named for Confederates. In fact, we have both a Union Street and a Republican Street.

However, those honored by Seattle street names are not without their own issues. Without even considering the streets named for the settlers and developers who displaced the Native American inhabitants, there are:

Returning to the issue of settlers and developers, in 2008, I wrote “Is it wrong to have a Negro Creek?” for Crosscut. (Tl;dr: Yes, it is, and stringers don’t write their own headlines.) After discussing the Chelan County creek in question, I started wondering just where the line should be drawn. (I mentioned the other day to my friend Thomas May that if it came to light that Beorma was found to be an unsavory character we could hardly change the name of Birmingham.)

[Added September 3, 2021: Upon further research, I have found out that George Kinnear was not responsible for the racial restrictive covenants applied to his subdivision — those were imposed decades later, after his death, by lot owners. I am leaving in the references to Kinnear I made in my Crosscut story, but changing those in this post.]

I wrote:

As for the settlers, though men like “Doc” Maynard (of the International District avenue and alley) may have maintained excellent relations with the city’s original inhabitants, Seattle is also home to neighborhoods like Hawthorne Hills and Kinnear, which are named for men (Safeco founder Hawthorne K. Dent and developer George Kinnear, respectively) who saw fit to exclude non-whites from owning property in their subdivisions.

Yet to eradicate all possible traces of offense from the map seems to be a losing proposition. Kinnear’s story isn’t cut-and-dried: he also served as captain of the Home Guard during Seattle’s anti-Chinese riot of 1886, which militia prevented Seattle’s Chinese from being forcibly deported, as had happened the previous year in Tacoma. And King County is named for a slaveholder, Franklin Pierce’s vice president William Rufus deVane King, though the county and state governments have managed to “rename” it after Martin Luther King, Jr.

Case-by-case, as these issues come up, seems the only sensible way to go. I am brought to mind of Liverpool’s Penny Lane, which was forgiven its association with the slave trade on account of its Beatles-related fame. Blanket proclamations can’t help but run into trouble.

I still do largely agree with what I wrote, although the idea of a renaming that isn’t really a renaming is less objectionable to me now. (My issue with King County’s name wasn’t that I thought William Rufus DeVane King deserved the honor, but that nothing was actually changed — the county’s name remained King County, not Martin Luther King Jr. County.) I would say this to those who still would want to rename Penny Lane: consider it named for the Beatles hit rather than for James Penny. (However, as it turns out, it wasn’t named for him in the first place, so the issue is moot.)

It makes you appreciate the system in Center City Philadelphia that much more — generally speaking, north–south streets numbered and east–west streets after trees.

So… besides Madison, Jackson, Stevens, and Lane — are any other Seattle streets ripe for renaming?

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.