This road, and the park through which it runs, Schmitz Park (or Schmitz Preserve Park), was named for German immmigrants Ferdinand Schmitz (1860–1942) and his wife, Emma Althoff Schmitz (1864–1959). Ferdinand was a banker, city councilman, and parks commissioner. He and Emma donated land — mostly, though not entirely, old-growth forest — to the city in 1908, forming the core (just over 55%) of the present park.

The Schmitzes had four children: Dietrich, Henry, Emma Henrietta, and Ferdinand Jr. A banker, Dietrich (1890–1969) became president of Washington Mutual in 1934 and retired as chairman of the board two years before his death. He was also a member of the Seattle School Board from 1928 (or 1930; sources differ) to 1961. Henry (1892–1965) was president of the University of Washington from 1952 to 1958. Schmitz Hall, the university’s administration building on NE Campus Parkway, was named in his memory in 1970.

According to the Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks,

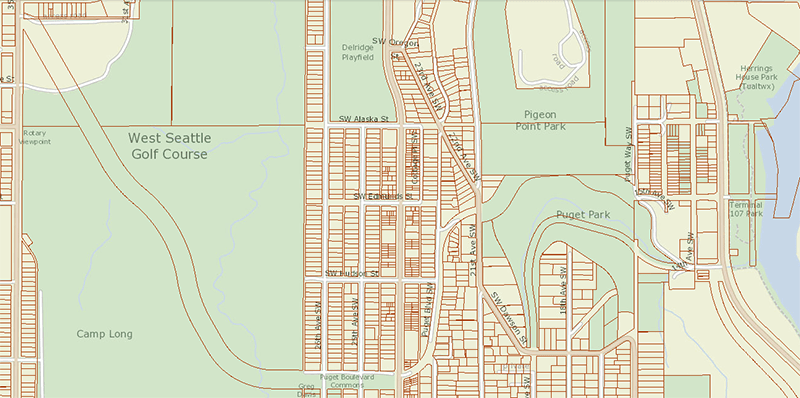

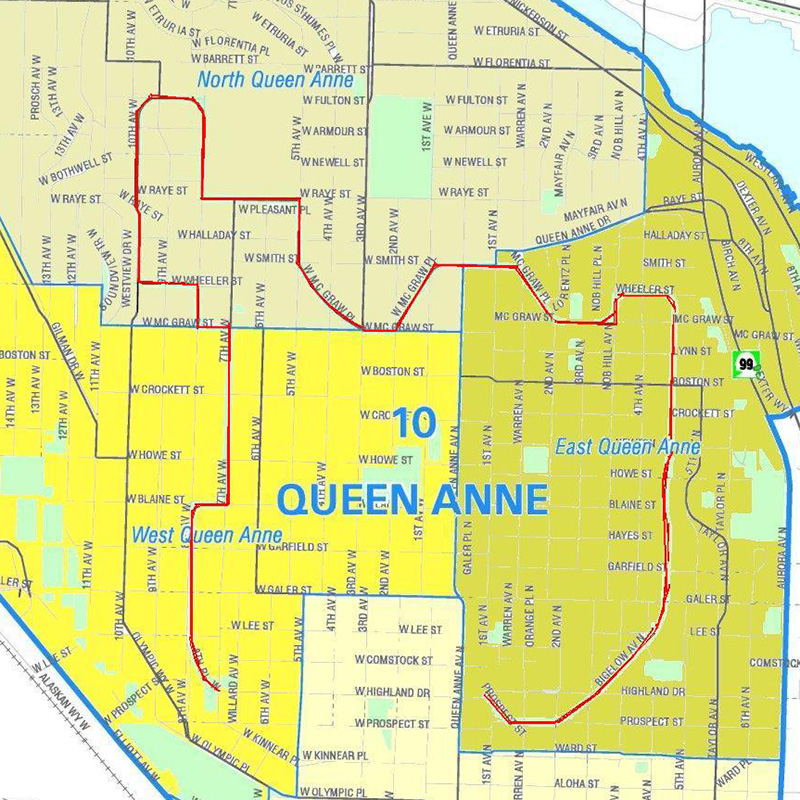

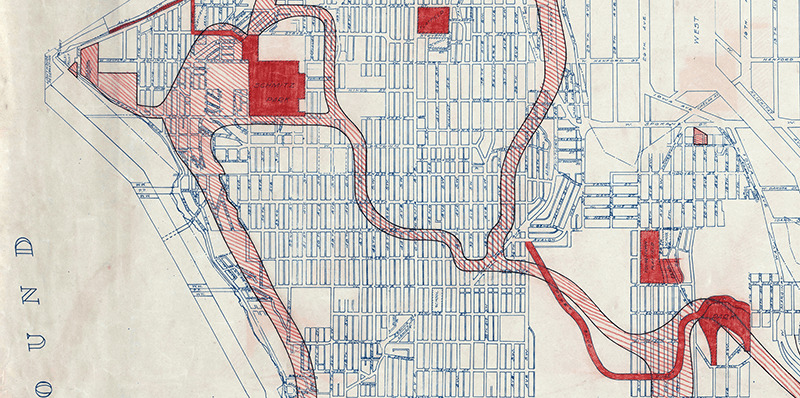

The roadway was originally envisioned as a continuation of the West Seattle Parkway, never realized, which would have connected Alki Beach to Lake Washington via a series of parkways. The built section is instead a short road that provided the only automobile entry to Schmitz Park, extending through an allée of trees and terminating at a pergola and shelterhouse.

The portion between 59th Avenue SW and 58th Avenue SW in front of Alki Elementary School having been closed in 1949, Schmitz Boulevard today begins at 58th Avenue SW and SW Stevens Street and goes not quite half a mile east, then southeast, then north, to SW Admiral Way and SW Stevens Street. It is closed to automobile traffic.

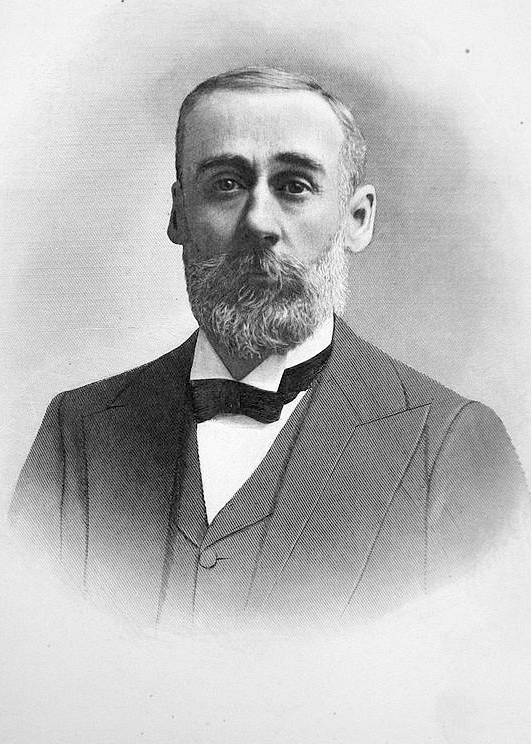

Emma Schmitz

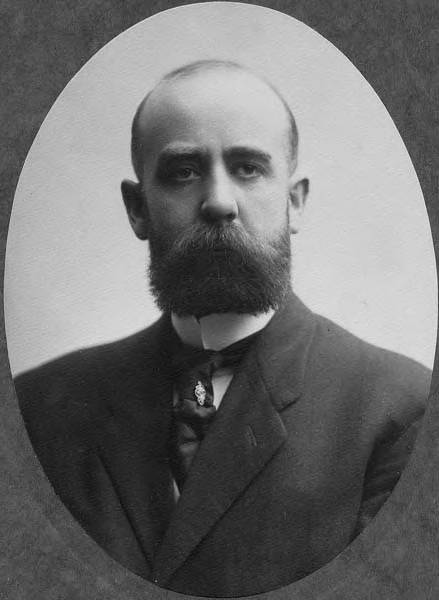

Ferdinand Schmitz

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.