Alaskan Way was originally Railroad Avenue. Jennifer Ott writes for HistoryLink.org:

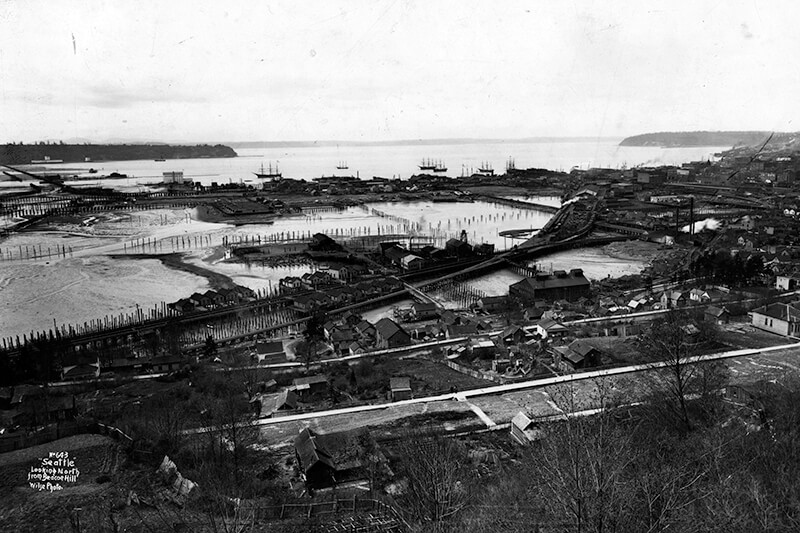

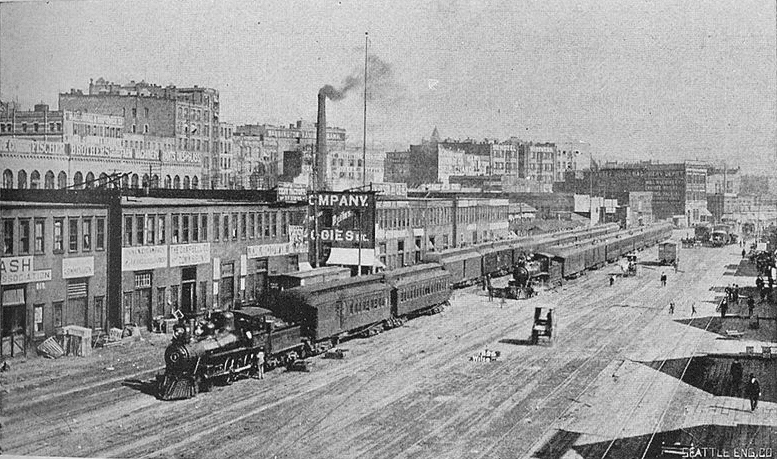

On the central waterfront a web of railroads grew out from the shore in the 1880s and 1890s as various railroads, including the Columbia & Puget Sound, the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern, and the Northern Pacific jockeyed for space at the foot of the bluffs that ended at the beach, where Western Avenue is today. In January 1887 the City Council passed an ordinance establishing Railroad Avenue, a street created, according to historian Kurt Armbruster, to provide space for the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern franchise to the west of the Northern Pacific’s franchise along the shoreline.

When the tidelands were platted in 1895, Railroad Avenue extended to Harbor Island and West Seattle, but:

- Sometime between 1912 and 1920 the Harbor Island portion was renamed W Florida Street (SW Florida Street today).

- In 1907, the West Seattle portion was renamed Alki Avenue.

- Sometime between 1912 and 1920 the West Seattle portion southeast of Duwamish Head was given its current name, Harbor Avenue.

In an article for Crosscut (now CascadePBS.org), Knute Berger explains why a new name was wanted for the remainder:

Seattle’s waterfront was unpaved — a beat-up plank road ran its length. There was no modern seawall — the street was built over the water. Train tracks were everywhere.… But the waterfront was undergoing a massive renovation. A seawall was being constructed, the shoreline filled in, the road made into a wide, paved boulevard.…

According to Berger and Ott’s articles, names that were proposed but were ultimately rejected included Anchors Way, Artery Way, Battery Way, Bois Boolong, Bread Street, Cargo Way, Chief Seattle Avenue, Cosmos Quay, Dock Street, Export Way, Fleet Way, Gateway Avenue, Golden West Way, Hiak Avenue, Klatawa Avenue, Maritime Avenue, Metropolis Avenue, Olympian Way, Pacific Way, Pier Avenue, Port Strand, Port Way, Port-Haven Drive, Potlatch Avenue, Puget Avenue, Puget Dyke, Puget Portal, Queen City Way, Roadstead Way, Salt Spray Way, Salt Water Avenue, Seawall Avenue, Seven Seas Road, Skookum Way, Steamship Way, Sunset Avenue, Terminal Avenue, Terrebampo Way, The Battery, The Esplanade, Transit Row, Voyage Way, Welcome Way, and Worldways Road. (Those in italics apparently came under serious consideration.)

So how did we end up with Alaskan Way? And why Alaskan instead of Alaska (the already existing S Alaska Street could have been renamed)?

The May 19, 1932, issue of The Seattle Times reports that the Seattle Maritime Association had run a renaming contest which received “more than one thousand letters… some of them contained scores of suggestions.” 4,868 names (including duplications) were received, and the judges selected four finalists, in order of preference: Puget Portal (one submission), Klatawa Avenue (one submission, from Chinook Jargon word meaning ‘to go, to travel’), Hiak Avenue (one submission, from Chinook Jargon word meaning ‘lively, quick and fast’), and Maritime Avenue (49 submissions [Maritime Way received 99 submissions but was not chosen]). The next day, the Times reported that the judges had chosen Maritime Avenue, and awarded the $20 prize to a Mr. B.I. Schwartz, the first to have suggested the name.

However, that July, a George D. Root proposed the name Cosmos Quay. At first, it was met with indifference, and then it seems the entire renaming project was put on the back burner until construction progressed. Somehow, when he restarted his campaign in 1934, Cosmos Quay became a leading candidate, and it was approved unanimously by the city council on January 14, 1935. An ordinance began to be drafted. But, as the Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted the next day, this was only because one councilmember, Frank J. Laube, had been absent… and he was adamantly opposed.

He wasn’t the only one. The Seattle Times published an editorial on January 20 headlined ‘City Locksmith Needed for Pronunciation Key’, which proclaimed that “to burden the waterfront stretch with a name that could be used and understood only through long courses in cosmogony, cosmology, etymology, and articulation would be a sad piece of nonsense for which there is no excuse.” The next day the Times reported that David Levine, city council president, said Cosmos Quay “no longer sounds so good to him. Many citizens have complained its meaning, as well as its pronunciation, mystifies them.” On February 4, according to the P-I, the council killed the ordinance and decided to leave Railroad Avenue as it was.

When the new street opened in 1936, the question of renaming came up again. Mayor John F. Dore appointed a committee that chose The Pierway, a suggestion that won a W.C. Denison, Jr., a prize of $50 from the mayor’s own pocket, but the final decision lay with the city council, which was not enthused. Pacific Way emerged as their favorite, according to a Seattle Times article on July 2, 1936, though a July 6 article in the same paper “the public apparently was not in accord with the idea.” On July 7, the Times reported that even though “at least seven votes [were] lined up in advance for the adoption of ‘Pacific Way’… with Council President Austin E. Griffiths contending for ‘Cosmos Quay’ or ‘Cosmos Way’,” an ordinance renaming Railroad Avenue “Alaskan Way” passed unanimously.

Alaska Way had been proposed in 1932 by the Puget Sound Travel Directors, according to an article in the April 13 issue of The Seattle Times. (As an aside, it was also proposed in 1931 by attorney John S. Robinson as an alternate name for Aurora Avenue N and the Aurora Bridge, according to a Times article on June 19.) It was also an entry in the Seattle Maritime Association’s aforementioned naming contest, submitted by Fred E. Pauli, manager of the Alaska Division of the Washington Creamery Company, according to a Times article on April 10, 1932. Then, in 1935, after Cosmos Quay had been rejected by the city council, the Alaska Yukon Pioneers endorsed Alaska Way (The Seattle Times, March 5), followed by the Whittier Heights Improvement Club (Times, March 7) and the Junior Alaska-Yukon Pioneers (Times, July 25). When renaming became a distinct possibility once again in 1936, as discussed above, the Alaska Yukon Pioneers passed a resolution in favor of Alaska Way (Times, July 4): “…It was here that the gold rush activity actually took place… put Seattle on the map and directly made possible the magnificent improvement now about completed.”

It came down to one councilmember, apparently. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported on July 7 that, the previous day, Robert H. Harlin proposed that the already-prepared ordinance renaming Railroad Avenue “Pacific Way” be amended to read “Alaskan Way” instead:

Councilman Robert H. Harlin, who offered the motion for adoption of “Alaskan Way,” said he preferred it to “Alaska Way” because it “recognizes the human element, honoring the men and women who pioneered the territory.” Although a majority of the council had informally agreed to support the name “Pacific Way,” sentiment crystallized rapidly in favor of “Alaskan Way” after Harlin’s statement.

Today, Alaskan Way S begins at the north end of E Marginal Way S, at the entrance to the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 30, and goes 2⅓ miles north, then northwest, to Broad Street, having become Alaskan Way on crossing Yesler Way. This is the Alaskan Way most people think of.

But, as they say, wait — there’s more! The right-of-way continues for another 1¾ miles, ending at W Garfield Street under the Magnolia Bridge, at the entrance to the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 91. From the Olympic Sculpture Park, which begins at Broad Street, to Myrtle Edwards Park, the right-of-way is taken up by park land and the tracks of the BNSF Railway — successor to the Columbia & Puget Sound; the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern; and the Northern Pacific, the railroads for which Railroad Avenue was originally built. Northwest of Myrtle Edwards, it’s entirely taken up by the tracks that run alongside Centennial Park. It isn’t until W Galer Street that there’s a city street in the right-of-way again, and Alaskan Way W only goes about ⅙ of a mile northwest from there to W Garfield Street. Even less than that is signed Alaskan Way, as the city has put up a sign for Expedia Group Way W where the W Galer Street flyover “touches down.” However, even though southeast of Galer the roadway runs first on Expedia property, then Port of Seattle property, the city appears to still consider it Alaskan Way W between the Expedia campus entrance and the north end of Centennial Park — a distance of just over ⅓ of a mile.

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.