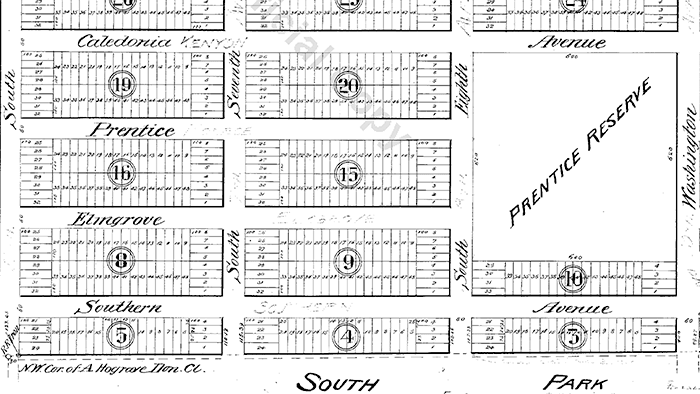

I enjoy writing posts on streets like W Commodore Way (I believe I am the first to have accurately identified its namesake), Division Avenue NW (I show that, even though it doesn’t divide anything from anything else today, it once served as Ballard’s eastern city limit for a few blocks), Loyal Avenue NW (I discover that it’s named not for the concept of loyalty, but for a baby girl whose first name was Loyal), and sluʔwiɫ (the University of Washington’s new Lushootseed-language name for Whitman Court). But sometimes I just like knocking something out quickly (I’m looking at you, W View Place and View Avenue NW). Sunset Avenue SW is another one of those. It originated in the 1888 First Plat of West Seattle by the West Seattle Land and Improvement Company, and the name simply refers to the street’s western view of Puget Sound; Vashon, Blake, and Bainbridge Islands; the Kitsap Peninsula; and the Olympic Mountains.

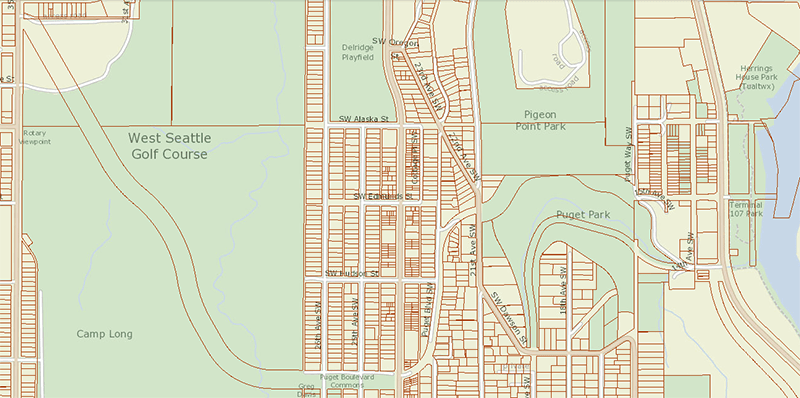

Sunset Avenue SW begins as a stairway at California Avenue SW, just across the street from Hamilton Viewpoint Park. Once the roadway begins up the hill, it goes ⅘ of a mile southwest to a dead end at the College Street Ravine southwest of 50th Avenue SW.

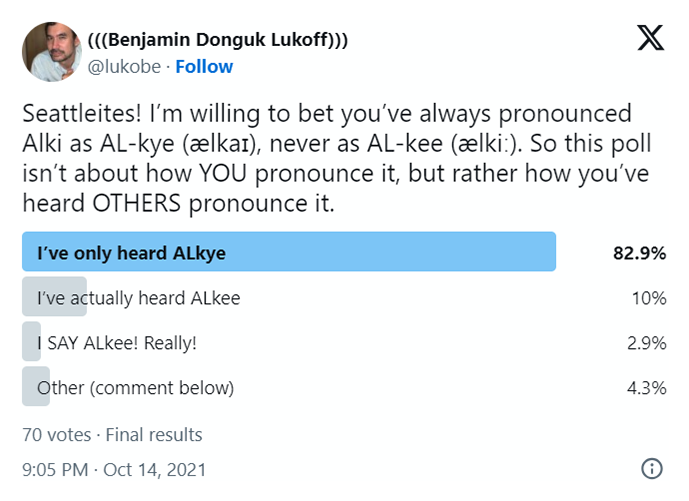

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.