N Clogston Way, which runs a mere 200 feet east from Green Lake Way N to a dead end, between N 54th and N 55th Streets, was named after a Union veteran of the Civil War, as Valarie Bunn of Wedgwood in Seattle History notified me tonight.

John D. Clogston served “with the 9th Regiment, New Hampshire Infantry. On the 13th of December, 1862, Clogston was wounded in battle at Fredericksburg, Virginia, losing part of his right hand. His injury was so severe that he was discharged on February 6, 1863.” He and his bride, Lucinda, moved to Seattle in 1889, just a few months after the Great Seattle Fire; he died 20 years later at the age of 71.

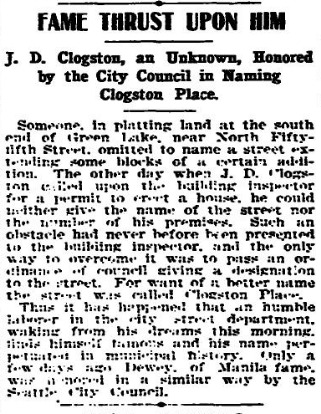

Bunn also pointed me in the direction of this Seattle Times article that appeared January 27, 1903, which explains how the street got its name:

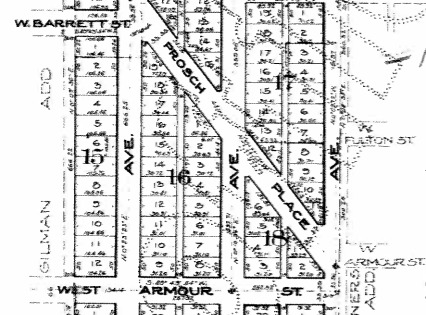

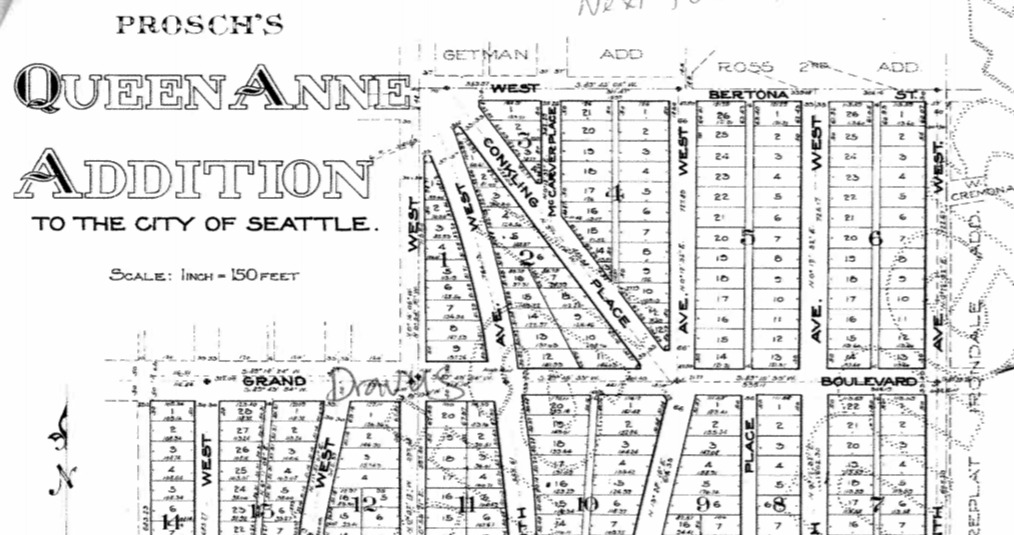

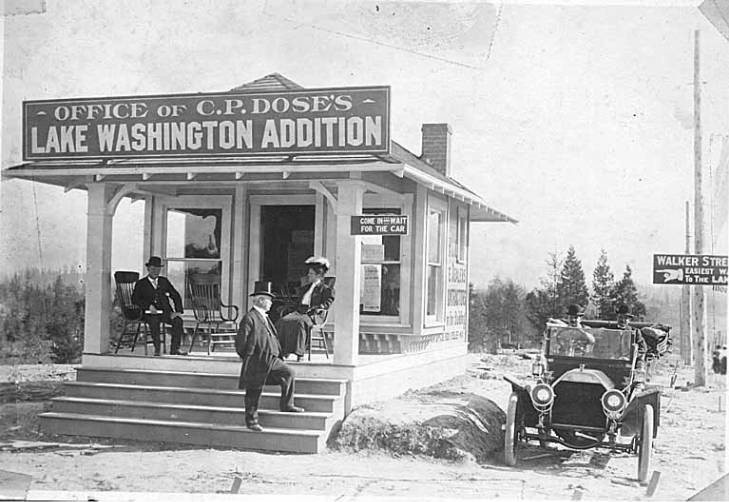

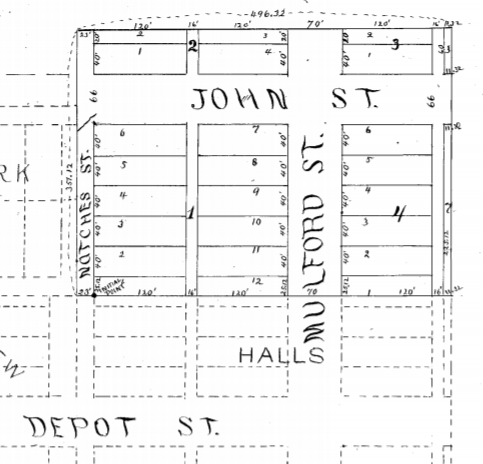

Someone, in platting land at the south end of Green Lake, near North Fifty-fifth street, omitted to name a street extending some blocks of a certain addition. The other day when J.D. Clogston called upon the building inspector for a permit to erect a house, he could neither give the name of the street nor the number of his premises. Such an obstacle had never been presented to the building inspector, and the only way to overcome it was to pass an ordinance of council giving a designation to the street. For want of a better name the street was called Clogston Place. Thus it has happened that an humble laborer in the city street department, waking from his dreams this morning, finds himself famous and his name perpetuated in municipal history. Only a few days ago Dewey, of Manila fame, was honored in a similar way by the Seattle City Council.

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.